Camp Morton – Civil War Camp and Union

Prison

Camp Morton – Civil War Camp and Union

Prison

1861-1865

Indianapolis, Indiana

Camp Morton – Civil War Camp and Union

Prison

Camp Morton – Civil War Camp and Union

Prison

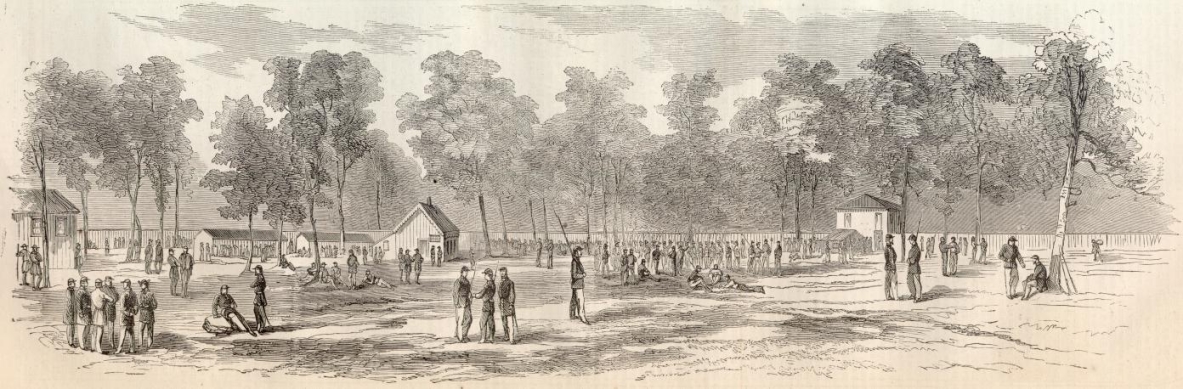

Guard and Guard-house at Camp Morton near Indianapolis,

Indiana.

The 60th Regiment Massachusetts Veteran Volunteers on guard.

August to November, 1864

Source: Prisoners of War, 1861-65

Camp Morton, an Indianapolis civil war training camp and later a federal prison for captured confederate soldiers, was located in the area now bounded by Talbott Avenue to the west, Central Avenue to the east, Twenty-Second Street to the north, and Nineteenth Street to the south. Samuel Henderson, the first mayor of Indianapolis, originally owned this thirty-six acre tract, which contained scattered hardwood trees of mostly black walnut and oak and at least four good springs. This area became known as Henderson’s or Otis’ Grove. A creek flowed through this property upon which, after it was dredged in 1837, become known as State Ditch. State Ditch was later nicknamed the “Potomac” by the prisoners of Camp Morton. State Ditch is no longer visible as it was made into an underground drain some years after the war.

In 1859, the State of Indiana took possession of this tract of land for the purposes of creating a State Fairground. By 1861, there were several buildings on the grounds as well as stables for livestock. On the north side of the grounds were long open-ended shed like structures to stable horses. The west end of the grounds contained stalls for 250 cattle and sheds for sheep and hogs as well as an exhibition hall. There was a large dining hall on the east end and a two-story office building near the center of the Fairgrounds. After the siege of Fort Sumter on April 12-13, 1861, recruiting stations were opened in Indianapolis in response to President Lincoln’s call for volunteers. Governor Oliver P. Morton, along with his newly appointed adjutant general, Lew Wallace, surveyed the town for a suitable location for the reception of these new volunteers. The State Fairgrounds was the only suitable place found near Indianapolis for this purpose. On April 17, 1861, Camp Morton was hastily put into operation and welcomed in the first volunteers. In order to accommodate the large influx of volunteers, some new sheds or barracks were built of green lumber in which four tiers of bunks were constructed on two sides of the shed extending seven feet toward the middle. Situated between the two rows of bunks were long dining tables. With this set-up, each barrack would hold about 320 men. The camp was surrounded by a high board fence with armed guards. As more and more troops started coming into camp, the barracks were supplemented with tents. Soon troops were divided up and given quarters outside the camp. Troop drills were first attempted in the confines of the camp, but the buildings and trees made this task difficult. An area just south of the camp was acquired for this purpose with good results.

*******

CAMP MORTON, NEAR INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA.(Woodcut Illustration from Harper's

Weekly, 9/13/1862, p. 588)

Illustration Courtesy of the Son of the South Civil

War web site. All Rights Reserved.

Note: The illustration above is explained on

page 587 of Harper's Weekly

CAMP MORTON.

ON page 588 we give a picture of CAMP MORTON, at Indianapolis, Indiana. This is the camp of instruction where the Indiana Volunteers are mustered and drilled before being sent forward to the war. It is situate(d) on the outskirts of the town of Indianapolis, and was formerly used as a fair ground. No State has done more nobly than Indiana; no camp has sent forward more or better soldiers.

*******

After the fall of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson in February 1862, there was a need in the north for detaining significant numbers of captured confederate soldiers. Governor Morton, in response to a telegraph request by Union General Henry W. Halleck, agreed to accept up to 3,000 prisoners who were to be quartered at Camp Morton. The job of converting Camp Morton into a prison camp fell to Captain James A. Ekin, an assistant quartermaster general of the United States Army. Additional barracks were hastily erected that had been used for temporary stables. Some of this work was not completed until after the prisoners arrived. The first group of prisoners arrived on February 22, 1862 with much fanfare in the city. The total number of confederate prisoners that were sent to Camp Morton during these next few days totaled 3,700.

Governor Morton summoned several partially filled Indiana regiments to guard these men, including the Fourteenth Battery of Light Infantry commanded by Captain Meredith H. Kidd, the Fifty-third regiment under Colonel Walter Q. Gresham, and the Sixtieth regiment under Colonel Richard Owen. Upon arrival of these troops at Camp Morton, Colonel Owen was appointed commandant.

The Indianapolis Journal, on March 4, 1862 described the health of the newly arrived prisoners as follows:

“Of the sick prisoners at the military prison and hospitals of this city, the greater proportion are Mississippians. Though some of the Tennesseans and Kentuckians are quite ill, their maladies are not so deep seated as those of the First, Fourth, and Twenty-Sixth Mississippi prisoners. These regiments were at Fort Henry, and at the time of the attack made upon it by Commodore Foote they retreated so rapidly that they left behind most of their baggage, including many articles of clothing much needed for their comfort. On arriving at Fort Donelson they were (thinly clad as they were) put at work immediately upon the fortifications, and were compelled to labor upon the trenches constantly. During the siege of the Fort, they lay in the ditches and rifle pits, day and night. Such exposure would produce disease in the ranks of the most able-bodied soldiers, but when incurred by men of feeble constitutions, the seeds of disease are so firmly planted that no medical skill can remove them. Of the latter class are those now in hospitals. Many are under eighteen years of age, and the large majority are persons of feeble constitution. They receive the best medical treatment, and the nursing care of female attendants; but in many cases, the best of attention cannot save them from the grasp of death.” (Terrell, p 548)

The sick prisoners soon overwhelmed the hospital quarters in the old power hall at Camp Morton. Some of the emergency cases were taken to the City Hospital, although sick and wounded Union soldiers already occupied most of the beds there. Hospitals were also opened in two buildings on Meridian Street. One of these, which became Military Hospital No. 2, was opened in the Gymnasium building on the northeast corner of Meridian and Maryland Streets. By early March, Hospital No. 3 was opened in the old four-story post office on Meridian Street near the corner of Washington. Better quarters were found for a hospital in a frame building on the corner of Curve and Plum Streets, east of the Bellefontaine car shops and north of Massachusetts Avenue. On April 3, patients and equipment from Hospital No. 2 were moved to this new location. In May, a new addition was erected on the north side of the present City Hospital and by May 24, the patients from the downtown hospital in the old post office and from the Bellefontaine hospital were moved there. Despite the best efforts of the hospital staff, many patients died probably in part due to their already poor condition when they arrived at Camp Morton. Hospital stewards were instructed to transmit to Colonel Owen and Adjutant General Noble a report of all the deaths with name of the deceased, date of hospital admittance, company, regiment, and list of any personal effects. Local newspapers also regularly listed the death of prisoners, but many names were listed as unknown.

Five lots were purchased near the City Cemetery for the interment of the Confederate prisoners who died at Camp Morton. This cemetery, which came to be known by one of its additions - Greenlawn, was located along Kentucky Avenue between West Street and the White River (now the location of Diamond Chain Company). An Indianapolis undertaker firm, Weaver and Williams, contracted to furnish plain wooden coffins at $3.50 a piece, and to deliver the bodies to the cemetery. At the cemetery, prisoners dug the twenty feet long trenches in which the coffins were laid side by side. A strong board carrying a painted identification number was placed at the head of each gave. No official ceremony was conducted for the dead, unless a prayer was offered by one of the prisoners.

By April 1, 1862 there were five thousand men in camp, including the guards. Prisoners continued to arrive during the spring and summer of 1862, including 1,000 men coming in after the battle of Shiloh. In the beginning, officers and enlisted men were housed together, but were later separated for security reasons.

Colonel Owen proved an able administrator and was liked by both guards and prisoners. Col. Owen established eleven rules for humane and sensible treatment of prisoners. This was before any federal regulations existed for the treatment of prisoners. As the war continued, the need for experienced troops was great. As a result, on May 26, 1862, Col. Owen’s Sixtieth regiment was ordered to active duty.

Governor Morton appointed David Garland Rose as the commandant to follow Col. Owen and was mustered in as colonel of the Fifty-fourth regiment on June 19, 1862. Also, during this time, replacement guards volunteered from all areas of the state. By the end of the first week of June, over four hundred had been sworn in for three months service, and there were more waiting for their companies to be completed. The continuous shifting of guard companies caused some problems at Camp Morton due to lack of experience. Some of these new guards were even reported to have wounded themselves with firearms. Colonel Rose was a strict administrator, and some prisoners disliked him intensely. On July 14, twenty-five prisoners were reported to have escaped during a stormy and rainy night. All but one were found and retuned to camp by July 18. During this time, there were a few incidents involving prisoners who strayed to close to the camp walls, one was shot after the prisoner was given the required three warnings.

On August 23, after both Union and Confederate parties agreed to a prisoner exchange, 1,280 prisoners left Indianapolis among a crowd of spectators. Other prisoners left in groups over the next six days, until the only prisoners that remained were prisoners whose names did not appear on any rolls, or sick prisoners and their nurses. The sick were later discharged during the first week of September. By this time, Camp Morton was emptied of all confederate prisoners and an immediate “renovation and purification” was begun by companies from the Fifth Calvary.

Starting in late September 1862, three thousand paroled union prisoners arrived at Camp Morton. By November 17, after having been formally exchanged, they were freed for service. By early December, Camp Morton was nearly empty.

In Early 1863, the empty buildings of Camp Morton were in disrepair. Due to the halting of prisoner exchanges at Vicksburg, additional prison spaces were needed for the large number of confederate prisoners still waiting exchange there. Even though Camp Morton was in desperate need of repair, prisoners were once again accepted, beginning on January 29, in lots of two to three hundred at a time. During this time, Colonel James Biddle, of the Seventy-first Indiana Regiment, commanded the camp. In April, all the new prisoners were ordered to City Point, Virginia for exchange.

The next group of prisoners arrived from Gallatin, Tennessee in late May, 1863. General Grant’s successful operation near Vicksburg sent 4, 400 confederates north to be divided between Camp Morton and Fort Delaware. Three trainloads of prisoners arrived on June 2, and the remainder arrived the following day. Among these new prisoners were 250 East Tennesseans who took that oath of allegiance and enlisted with the Union army. Fifty of these men enlisted in the Seventy-first Indiana, 50 in the batteries, and155 in the Fifth Tennessee Cavalry. After the capture of Confederate General John H. Morgan on July 23, 1863 in Ohio, 1,200 of Morgan’s men were sent to Camp Morton. The arrival of Morgan’s men created a carnival atmosphere in the camp for a time. By August there were about 3,000 prisoners at Camp Morton. On August 17 and 18, over 1,100 prisoners, including most of Morgan’s raiders, were transferred to Camp Douglas. About 1,500 prisoners remained in the run downed camp. Over crowded conditions at the camp lead to increases in sickness and disease. Hospital space was also inadequate to accommodate the growing number of sick. The new addition to the City Hospital, that was built in 1862 specifically for the sick of Camp Morton, was now being used for wounded and sick Union Soldiers.

The overcrowding continued at Camp Morton during the summer and early fall of 1863. Several escape attempts by prisoners were made during this time. One group of prisoners, after working twelve days on a tunnel under the north fence of the enclosure, was betrayed on the eve of the escape. Other groups tried to escape and thirty-five men got away safely during this time.

View inside prison at Camp Morton near

Indianapolis, Indiana, the summer and autumn of 1864.

Note substantial and comfortable barracks

Source: Prisoners of War, 1861-65

Colonel Ambrose A. Stevens was appointed the new commandant on October 22, 1863. With the halting of exchanges of all prisoners north and south, the prisoners at Camp Morton would remain there. Then Adjutant Thomas Sturgis, while a member of a Union regiment on guard detail at Camp Morton, describes the conditions in the camp during the summer and autumn of 1864:

“At the time of which I write the cooking at Camp Morton was done by my details. We baked daily from 5,000 to 7,000 loaves, about six inches cube, of good white bread, which gave to each prisoner a loaf, appetizing and healthful. Our own men were then drawing only hard tack as an equivalent. On their arrival the prisoners were given necessary clothing and blankets. Each man received one of the latter, and as two usually bunked together, they joined forces. As the cold weather of autumn approached we made a further issue of a blanket apiece, and some of the men fashioned the old ones into capes or cloaks, and the sight of a sturdy Confederate strolling about with the Uncle Sam’s U.S. branded between his shoulders was not uncommon.”

View inside the prison at Camp Morton, the summer

and autumn of 1864.

Note that during this period of largest number confined there was no crowding,

but on

the contrary ample space for air and exercise

Source: Prisoners of War, 1861-65

In July, 1864 Camp Morton housed 4, 900 prisoners, over half of this total had arrived since May. The renovations and improvements at the camp had not been made on a scale to accommodate many of these new prisoners. A high number of malaria cases were reported during this time. Reforms at Camp Morton were ordered by Union Army medical personnel, which included recommendations of enlarging the camp, building of new hospital wards, and a supply of vegetables or “antiscorbutics” for the prisoners to prevent scurvy. Some of these reforms, however, were never instituted.

View inside prison at Camp Morton, the summer and

autumn of 1864.

Note prisoners are all supplied with blankets

Source: Prisoners of War, 1861-65

On the night of November 14, a mob of fifty or sixty prisoners rushed toward the fence while hurling stones and bottles filled with water at the surprised guards. Before reinforcements could reach the guards, the prisoners escaped over the fence and into the woods. An all night search party found some of the escapees, but thirty-one were never found.

The winter 1864-1865 was very cold. On New Years day, 1865, the temperature dropped to 20 degrees below zero along with a severe snowstorm. Extra straw, blankets, and wood for the cast iron stoves were secured for the barracks, but the winter hardships continued. The winter proved to be very cold with the last snow recorded on April 16. As the weather warmed, conditions improved slightly. Prisoners continued to make several escape attempts and some were successful, including an escape by a group of men through yet another tunnel.

Prisoner exchanges began again in February and March of 1865, although some prisoners refused to be exchanged if it meant going back to the Confederate lines. By April 1, 1865, 1,408 prisoners remained at Camp Morton. With General Lee’s surrender on April 9, all of the remaining prisoners were released after they were administered the oath.

Here is an interesting Camp Morton side story. In

1863 the City of Indianapolis placed a tower on a three story building known

then as the Glenn Block building on top of which sat a watchman for the purposes

of spotting fires and giving an alarm if one should break out. During the

time when prisoners were held at Camp Morton, this tower watchman had special

orders to also keep his field glass trained on the prison, which was about two

miles to the north of the tower. There were rumors spreading that if the

prisoners had escaped, they would pillage and set fires in the city. At

the first site of danger, it was then the duty of the watchman to sound the

alarm, whereupon the citizens would assemble at the armory and receive their

guns and ammunition for the protection of the city. There was also talk

that if the confederate prisoners had escaped and set fire to the city, that

they would also try to cripple and damage the fire suppression equipment.

Because of this threat, each member of the fire department carried a revolver

for a time (source: http://www.indygov.org/eGov/City/DPS/IFD/History/Pages/home.aspx).

After the War, Camp Morton was opened back into the State

Fairgrounds, were it remained as such until 1892 when a new State Fairgrounds was opened further

north at 38th Street and Fall Creek. The old State Fairground property was sold for $275,100 and

was divided

into residential lots. This area of

Indianapolis is now known as Herron-Morton Place.

The State Fair in 1870. It was then located on the site

of old Camp Morton, between

Delaware and New Jersey street, from 19th to 22nd streets.

Source: Indiana Historical Bureau, date unknown

No official marking of the old Camp Morton was initiated until 1916, when the teachers and students of Indianapolis School Forty-five marked the site by placing a boulder at Alabama and Nineteenth Streets, with the following words inscribed into the stone:

Camp Morton

1861-1865

ERECTED BY SCHOOL

FORTY-FIVE

1916

An Indiana Historical Bureau marker was, in

1962, installed in the same area to also mark the Camp Morton location.

This historical marker along with the original stone boulder are now

located at the Herron-Morton Place Historic Park, in the 1900 block of North

Alabama Street.

Indiana Historical Marker: Camp Morton - ID No. 49.1962.2

Herron-Morton Place Historic Park

Picture Taken March 27, 2004

Four boundary markers were installed on July 15, 2000, by the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War, Ben Harrison Camp 356, in cooperation with the Sons of Confederate Veterans, to delineate the four corners of the old Camp Morton property. A boundary marker dedication ceremony was held at the park on October 25, 2003.

The Sons of Union Veterans Southwest Boundary Marker of Camp

Morton

19th Street and Talbott Avenue

In 1911, Sumner Archibald Cunningham, the editor of Confederate

Veteran Magazine, received permission to place a bronze memorial tablet in

honor of the very well liked Camp Morton commandant, Colonel Richard Owen, in

Indianapolis. Contributions were so great that a bronze bust of Colonel

Robert Owen (shown to the left) was substituted for

the tablet and placed in the Indiana State House.

Cunningham commissioned Belle Kinney as the sculptor. The bust was

dedicated in 1913 in the presence of many veterans, both north and south.

The bust bears the following inscription:

COLONEL RICHARD OWEN

COMMANDANT

CAMP MORTON PRISON 1862

TRIBUTE BY CONFEDERATE PRISONERS

OF WAR AND THEIR FRIENDS

FOR HIS COURTESY AND KINDNESS

A replica of this bust is located in the Indiana Memorial Union on the campus of Indiana University.

The City Cemetery and Greenlawn, where the Confederate dead of Camp Morton were buried, ceased to be used as a public cemetery in the 1860’s when the new city cemetery, Crown Hill, was opened. Some of the Confederate bodies were later exhumed and returned to relatives in the south, but most remained buried at Greenlawn. Over time, the old City Cemetery and Greenlawn became neglected and overgrown with weeds. Additionally, commercial growth was encroaching on the cemetery. In 1870, the Vandalia Railroad moved two rows of graves in Greenlawn to another section of the cemetery to make way for an engine house and additional tracks. In 1906, Colonel William Elliot was detailed by the War Department to locate the burial place of the Confederate dead. He determined that a plot about forty-five feet wide by two hundred feet long was the place where the 1870 reinterments had been made. This place was enclosed by an iron fence, and in 1912, the Federal Government erected a monument there. Industrial development continued to encroach on this small cemetery plot, so in 1928, permission was granted by the Federal Government for the Southern Club of Indianapolis in cooperation with the Board of Parks Commissioners to move the monument to Garfield Park. The names and regiments of the dead soldiers are listed on bronze tablets around the base of the large monument. The shaft bears the following inscription:

PAX

ERECTED

BY THE

UNITED STATES

TO MARK

THE BURIAL PLACE

OF 1616 CONFEDERATE

SOLDIERS AND SAILORS

WHO DIED HERE

WHILE PRISONERS

OF WAR

AND WHOSE GRAVES

CANNOT NOW BE

IDENTIFIED

Confederate Monument in Garfield Park - Indianapolis, IN

Near the Southern Avenue Entrance

The War Department exhumed the remains of the Confederate prisoners buried in Greenlawn and moved them to the northwest corner of Lot 32 at Crown Hill Cemetery between the years 1928 and 1931. This area is also referred to as the “Confederate Mound.” The last of the remains were laid to rest in the Confederate Mound, with full military honors, in October 1931. Upon the final closing of the tomb at the Confederate Mound, there were plans to move the Confederate monument from Garfield Park to the Confederate Mound, but due to cost over runs in the removal project as well as the Great Depression, this was not done. There is also information to suggest that the Garfield Park monument was not moved to the Confederate Mound because the mass grave with its wooden boxes full of bones might have collapsed if the monument was placed directly on the grave.

UPDATE: The Garfield Park Confederate “Peace” Monument, which was a federally paid for grave marker, was illegally removed, and subsequently destroyed, by Mayor Joe Hogsett and the City of Indianapolis, on June 8, 2020. Several legal challenges to protect this monument were undertaken prior to its removal, but in the end, the City of Indianapolis chose to ignore federal law and had the monument removed. After removal the monument was stored in pieces for a time, but was later destroyed and scrapped out by a local metal recycler. See the links below for local media coverage of the removal of this monument.

https://fox59.com/news/crews-work-to-dismantle-confederate-monument-at-indys-garfield-park/

https://fox59.com/news/confederate-monument-in-indys-garfield-park-will-be-removed/

https://fox59.com/news/removal-of-confederate-monument-in-garfield-park-draws-variety-of-opinions/

While I do not personally agree with some of the

conclusions of this author, this is an excellent and well researched history of

the Garfield Park Confederate “Peace” Monument, which was written in August,

2017.

https://paulmullins.wordpress.com/2017/08/28/race-reconciliation-and-southern-memorialization-in-garfield-park/

In 1993, after a four-year project first initiated by two Indianapolis police officers, Detective Wayne Sharp and Sergeant Stephen Staletovich, additional markers were installed at the Crown Hill site listing the names and regiments of the dead. The original inscription on the monument was covered with the current bronze plaque in 1993 (shown to the left below). The original inscription was engraved in the granite and read simply: "Remains of 1616 unknown confederate soldiers who died in Indianapolis while prisoners of war." A list of Confederate Soldiers and Sailors who died at Camp Morton and are now buried at Crown Hill Cemetery can be found below.

Confederate Burial Plot, Northwest Corner of Lot 32

Crown Hill Cemetery - Indianapolis, IN

Sources for the above Camp Morton History:

Camp Morton 1861-1865 - Indianapolis Prison Camp, by Hattie Lou Winslow and Joseph R. H. Moore. Indiana Historical Society, Indianapolis, IN, 1995. Originally published in 1940 as volume 13, number 3 of the Indiana Historical Society Publications.

Indiana in the War of the Rebellion, Vol. 1, Report of the Adjutant General, by W. H. H. Terrell. Indianapolis, IN, 1869.

Prisoners of War, 1861-65, by Thomas Sturgis. The Knickerbocker Press, New York, 1912.

Confederate Burials at Crown Hill Cemetery - Internment.net (added 10/29/07)

Crown Hill Cemetery Project - Marking of the Confederate Graves

Greenlawn Cemetery - List of Confederate Soldiers and Sailors who Died at Camp Morton (Not Complete)

Indiana State Archives - Camp Morton

Cornell University - from the Century Magazine - Open Letters - The Camp Morton Controversy

In Memoriam - Confederate POWs of Camp Morton, Indiana

Statue of Colonel Richard Owen at Indiana University, Bloomington

Biography of Colonel Richard Owen

Sumner Cunningham & Our Confederate Heritage

Sons

of Union Veterans of the Civil War - Ben Harrison Camp

Camp Morton Boundary Marker Dedication (added 12/4/05)

Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War, Department of Indiana

Indiana Division Sons of Confederate Veterans

Moment of Indiana History - Camp Morton (added 10/27/05)

Son of the South Civil War Web Site (added 10/27/05)

Camp Morton Book Reviews from Thunder From a Clear Sky (added 10/24/06)

This Web Site Has

Been Viewed By

This Camp Morton Web Page was designed and is maintained by Tim Beckman, your web host. It has been my honor to present to you this history of Camp Morton. If you are searching for a soldier who might have died at Camp Morton, please check the links above for a complete list of names. I do not have any such lists in my possession.

If you have any comments about this page, please send me an e-mail to the address below. I look forward to hearing from you.

May

we always remember the sacrifices made by all men, both North and South

May

we always remember the sacrifices made by all men, both North and South

Some of the clipart seen on these pages are from: The Civil War Clipart Gallery